Dutch kids can't read because of capitalism

What's behind some appalling new literacy statistics

The reading skills of Dutch students are bad and getting worse. New data shows that Dutch kids are among of the worst readers in all of Europe: only students in Greece, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania score lower.

One third—one third!—of Dutch fifteen year-olds are “insufficiently literate.” Meaning they won't be able to read safety instructions at work or the instructions on medical prescriptions.

Why? Pandemic school closures? Smartphones? Migrants? The teacher shortage?

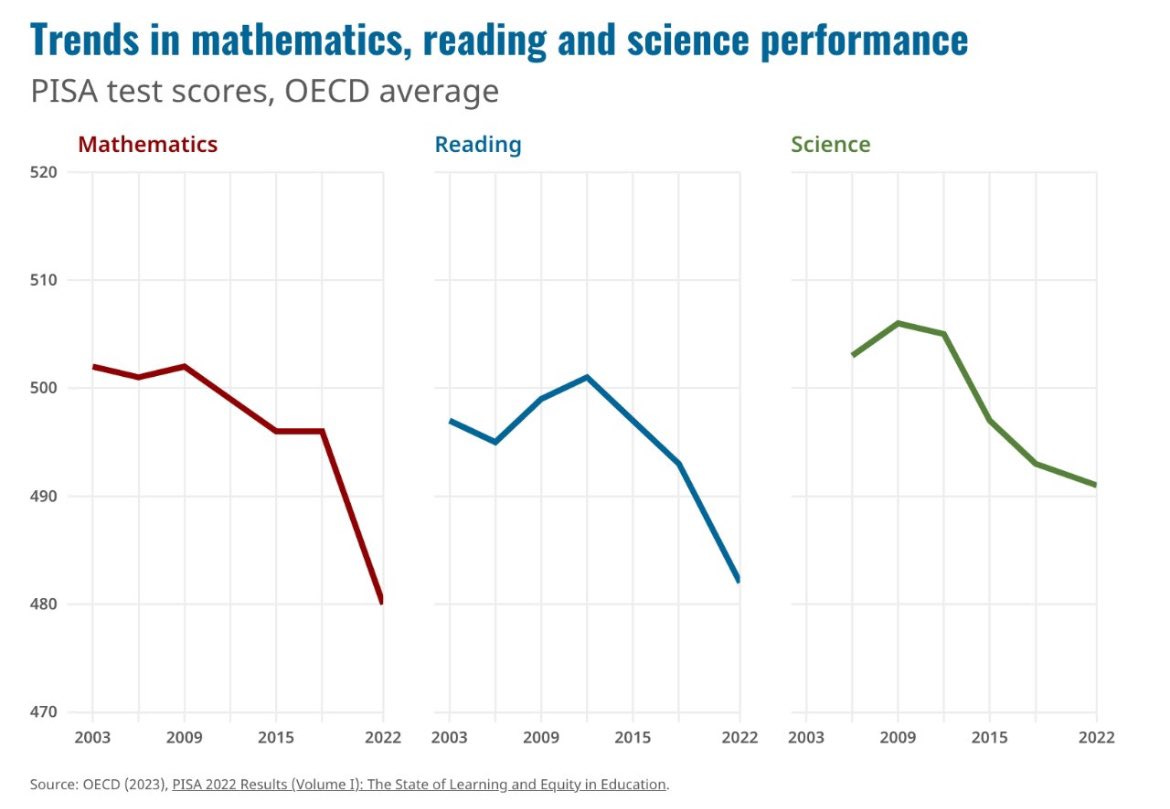

Issues like some of these “make solving the problem more complicated, but are not the cause,” Margreet de Vries, a former policy officer at the Ministry of Education, wrote on LinkedIn. All countries and classrooms face these problems to some extent—and test scores are indeed falling all over the world.

But Dutch scores started falling twenty years ago, long before Corona or Tiktok. So what makes the situation in the Netherlands so bad?

The free market in public schools

Public education curriculum in the Netherlands has been privatized. Schools are required to reach educational targets—students must pass evaluation tests. But there is no centralized or governmental control over the content of what is taught in the classrooms.

Every year since 2006, Dutch schools have received funding in the form of a “lump sum,” which is just what it sounds like. The idea was dressed up as a scheme to give schools more autonomy, but it sounds to me like the real driver was “small government” politics—and an attempt to reduce the administrative and legal costs of the previous “declaration funding” system, when the Ministry of Education paid teachers directly.

With autonomy comes opacity. “The disadvantage is that no one now knows what happens to education money. It ends up in a black hole,” Econometrician Hans Duijvestijn told Follow the Money this year.

Schools wound up with autonomy, piles of cash, and no plan. For-profit publishers charged in, producing huge amounts of material: apps, dashboards, lesson packages, video content, textbooks, digital programs, etc.

The more education products these companies sell, of course, the more money they make. They’re incentivized to sell, not educate, and there’s no system to determine whether or not their methods work, or are scientifically proven. Most often they are not. The government also stripped funding for the “public school guidance services” which taught teachers how to teach, and schools stopped hiring teachers—the most expensive line item in any school budget. Per Duijvestijn:

Schools have turned into businesses.

The educational “innovations” used to teach students are sold to schools through distributors. There are only two that matter, and their sales tactics sound as gross as what goes on in American pharmaceuticals. The co-owner of Heutink, one of these distributors, is listed in the Quote 500 (an annual list of the richest Dutch people), worth 160 million euros. Speaking of gross.

According to de Groene Amsterdammer:

The introduction of lump sum financing and the establishment of a free trade in teaching packages and educational advice creates a textbook example of an imperfect market, where primary schools rely on a bag of government money, but are almost completely dependent on an oligopoly.

Low expectations

This Opioid-salesman-esque situation playing out in the educational system—just one branch of massive Dutch bureaucracy—makes things even more complicated. The Dutch system only functions as well as it efficiently categorizes people, or so the system believes. This, by the way, is why Dutch people are always saying “not possible” (niet mogelijk). The system cannot cope with outliers; it wants you to fit in a box so it knows what to do with you.

Schools in the Netherlands are “weighted” based on factors like the country of origin and educational level of parents, and far fewer poor students are expected to reach target educational levels—which means passing evaluation tests—than rich students. The government simply does not expect underprivileged children to read well because it categorizes them as being unlikely to. As Eva Naaijkens, principal of the Alan Turing School, wrote on LinkedIn:

Because of the way in which schools are assessed, we normalize the fact that ‘vulnerable’ children perform much less well. They swim straight into the trap of low expectations.

And here's good example of one of the endless ways the Dutch system categorizes people:

At many schools, children are pre-sorted early. For example, they are not offered the alphabet in their nursery groups, their phonemic awareness is insufficiently developed due to a lack of goal-oriented activities... A child soon ends up on his or her own learning path and the disappointing results are seen as characteristics that belong to the child.

On top of private companies who are incentivized to sell as much shit to schools as possible, the part of public education that remains public, in control of the government and operating in consideration of the health of society, predetermines that some kids will not be expected to read well because of where they were born, and who their parents are.

Who's to blame?

“It would be too easy to blame the sharp decline in reading skills of Dutch young people on Dutch education,” opens an bizarre editorial in Trouw, which goes on to blame our tragic literacy rates on video game vloggers who speak broken English, social media, parents, and a sort of pathological pampering of our young:

The Netherlands distinguishes itself from other countries in its indulgence towards children.

I’m not sure how one third of teenagers being functionally illiterate relates to indulgence, but anyway. You can also blame privatization and bureaucracy, as I have above. Or, smartphones, migrants in the classroom, woo-woo teachers, or woke students themselves.

No matter who you blame, many people seem to agree that we need better, higher-level government system, like a national plan, “a government that takes back control of education and leaves less to school boards.”

Can the government take back control? It certainly doesn’t want to.

Literacy didn’t rise to the level of public debate in last month’s elections; party platforms are weak on the topic. As far as I can tell the only educational issue that has come up in the mayhem of the cabinet formation debate this week was Geert Wilders swearing up and down that he won’t actually close Islamic schools if he gets the chance. The Minister of Education, the guy who wants to change the language of instruction from English to Dutch at all universities in the Netherlands, has been silent on the topic.

The head of the powerful Secondary Education Council wrote last year LinkedIn of PISA scores:

These kinds of studies and international comparisons are unusable for basing policy on.

(Experts disagree.)

Jindra Divis, the chairman if the Curriculum Development Foundation (SLO) which sets the objectives for what students learn told de Groene Amsterdammer:

We cannot tell school material providers how to organize their methods. That's not our job. We must not disrupt the market.

The public education market!

With so many culture-war-ish factors like smartphones and Corona school closures to blame, and bureaucrats, like all bureaucrats ever, incapable of admitting there’s clearly something wrong with the system, it seems like nothing will change soon. Reading skills will only get worse. And we’ll have to see what comes of it all in a few more years, when teenagers with such poor reading skills become adults, and workers.

De Groene Amsterdammer looks on the bright side: “The good news is that more and more schools are taking matters into their own hands. They are moving away from ready-made teaching methods and are starting to create lessons themselves again.”

The bad news: laying the responsibility for an improvement in reading skills in the hands of school managers is exactly where the broken system wants it.

🔥 Hot Linkjes

Politics

This chart is from 2019. As of then, Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom was the most right wing party in… the entire Western world. (Sahil Chinoy / The New York Times)

The top searched term for 2023 according to Google Trends for the Netherlands was stemwijzer, the interactive voting guide. Which goes to show—in a fragmented system with so many political parties, people need a lot of help figuring out who to vote for. (Google)

Culture

Netflix now publishes a bi-annual report of its most-streamed series and moves. I spotted some Dutch hits on the list: Dirty Lines, Undercover, Women of the Night, the Marriage Escape, and Black Book, to name a few.

A long read / podcast on the origins farmer protests, and the current political situation in the Netherlands. I didn’t realize just how much the government had forced livestock farms expand, how much debt many farms had taken on, or how this led to serious feelings of betrayal when the government changed course. (Paul Tullis / The Guardian)

Speaking of farming, there’s a floating farm near downtown Rotterdam. You can buy milk and cheese from their cows at a nearby stand. (Mike Corder And Melina Walling / Quartz)

🥳 Leuke Dingetjes

Eurovision 2024

Happy hardcore rapper Joost Klein will represent the Netherlands at the Eurovision Song Contests 2024. He is already an accomplished performer, with big hits and experience playing big festivals. This background should help avoid the disastrous outcome last year, when a novice duo, Mia Nicolai and Dion Cooper, crashed and burned on stage.

Lots of debate here in America, as well, on whether the predominate methods used to teach reading, in the last 10-20 years, have helped or hurt literacy. I’m sorry it’s happening in your neck of the woods too. Thank you for sharing.

This was a great summary. When I was doing my teacher training (I'm an English teacher, "eerstegraads bevoegd") I did a few courses with the Dutch track and there was huge debate about teaching reading skills (leesvaardigheid). My impression is that throughout the years, gradually gradually, teachers have been accommodating to the final exam ("teaching to the test"), and the final exam has been accommodating to the weakening results, leading to a downward spiral. Even when I was at school, I remember thinking the way reading skills was taught was just silly - insisting that the most important information is always in the first sentence of the paragraph, for example. It really very often isn't. Anyway, it's a multifaceted problem and this is just one part of it, but I am surprised by how little it gets mentioned.