Who's to blame for the Dutch housing crisis?

How a plan to build 1 million new homes by 2030 derailed in six months.

The population of the Netherlands is booming. Nineteen million people will live in the country by the end of 2040, up from 17 million in 2021, and there is already a shortage of 300,000 homes.

This the direct result of disastrous housing policy over the last decade.

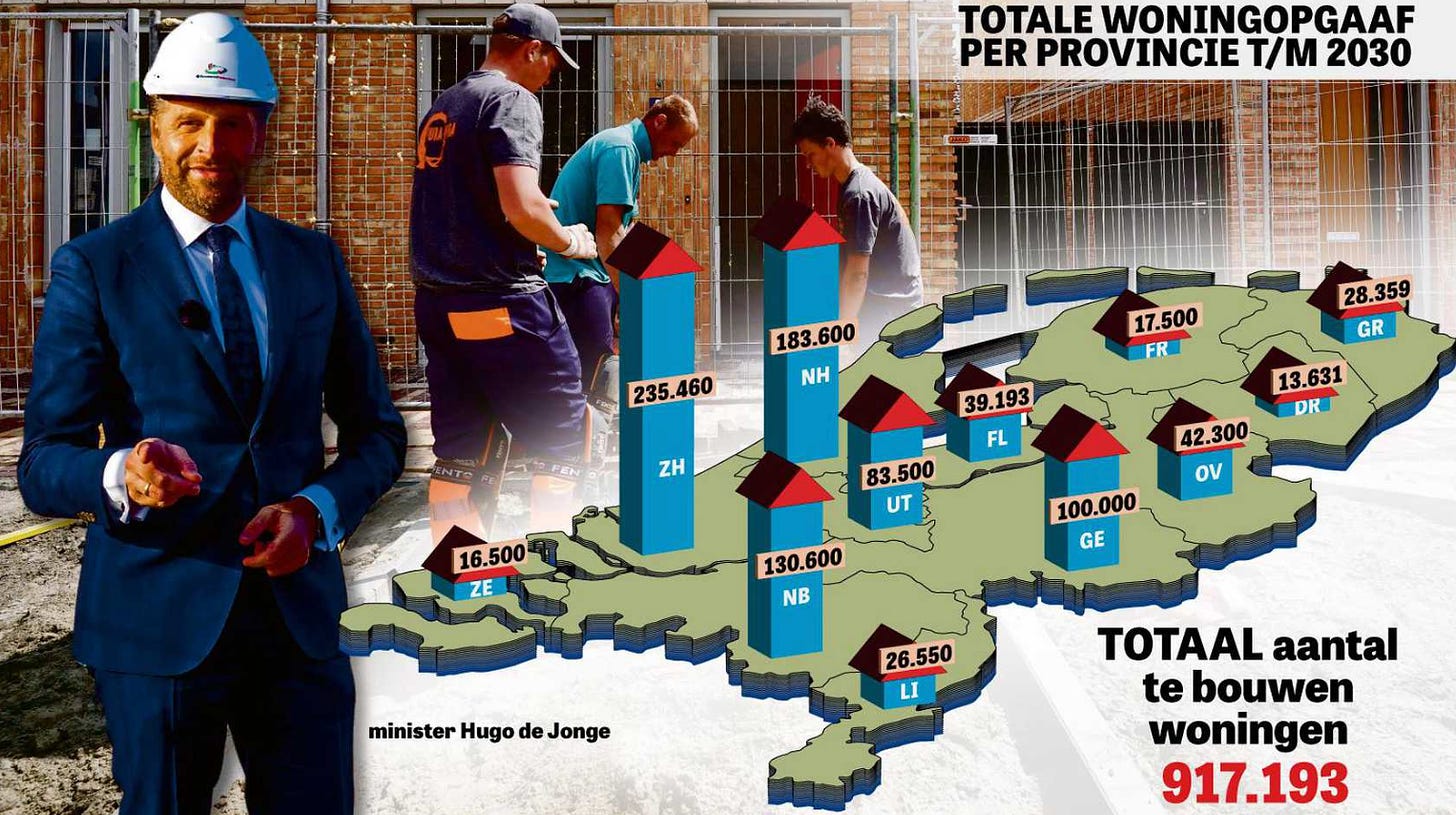

Last October, Minister of Housing Hugo de Jonge (who you might recognize—he was Minister of Health during the pandemic), announced an ambitious, 11 billion euro plan to build 900,000 new homes by 2030.

But half a year later, it’s clear that it will be impossible to hit that number.

The Economic Institute for Construction (EIB) has said that building 900,000 homes in the next seven years is “virtually unfeasible.”

Last week, de Jonge said that he foresees “a dip in housing production” next year. While 90,000 homes were built in 2022, that number is expected to drop 45,000 in 2023.

It’s Mark Rutte’s fault

Last week on Op1 de Jonge was asked about the causes of the housing shortage, and his answer was super interesting. It essentially amounted to an admission that he thinks his boss, Prime Minister Mark Rutte (and his previous cabinets) fucked things up.

I think part of the cause is simply the fact that we have not adequately directed public housing in recent years, we have not sufficiently accounted for what is actually needed, how many homes should we actually build, what can people actually afford. We have had far too much faith in municipalities… we have had far too much faith that in the market…

And this is not the first time he’s said this kind of thing.

Stef Blok, Minister of Housing in previous Rutte cabinets, introduced a number of housing reforms (including taxing public housing and selling off large swaths of affordable properties to foreign investors) which slashed the availability of housing; since 2015 a full 100,000 (!) social housing units have disappeared.

Blok got away with these initiatives thanks to a public conversation about a public housing surplus and ‘skewed living’ (scheefwonen), the idea of social housing residents continuing to live in subsidized housing once their incomes get too high for it, something presented as sneaky fraud.

These reforms were right in line with the disastrous Rutte-era conservatism I wrote about last week, a philosophy which basically goes like: save money with policies that make life hard for poor people and the poor people will help themselves.

Blok consolidated the Ministry of Housing into another Ministry for a period of time. In 2017, at the end of his term, he infamously, proudly, said:

I am the first VVD member who has made an entire ministry disappear!

Yikes! He believed that housing was so under control that a centralized ministry wasn’t even necessary. In the same interview from 2017:

Almost all decisions about housing, such as zoning plans, are made at the municipal and provincial level. [The Ministry of Housing] could actually have been abolished in 1965, after [post-WWII] reconstruction.

Big time yikes again!

This is why de Jonge directly pointing to a lack of centralized housing policy on a talk show is such a big deal. He broke ranks with the prevailing “wisdom” that got the

Netherlands into this housing mess—and many others—in the first place.

But in practice…

How the plan to build 900k homes fell apart

Some really basic obstacles are getting in the way of housing construction these days: inflation, supply-chain disruptions, expensive building materials, labor shortages.

All of this means higher costs for buyers—who are also facing sky-rocketing mortgage interest rates. The total number of new homes sold is expected to decrease by half in 2023 compared to the recent average.

De Jonge’s plan is (naturally) focused on affordable housing, and requires two-thirds of new construction to be capped at a purchase price of 355,000 euros, rent at 1,000 euros. But civil servants don’t build homes, real estate developers do. And many aren’t playing ball at these prices.

Permitting is also its own little disaster. Staff shortages at municipalities mean building permits are hard to get; in 2022 municipalities issued 63,000 permits for new homes—16 percent less than in 2021. The average lead time from the granting of a permit to building is about two years.

It gets worse: last November, the Council of State threw out the nitrogen exemption for building permits. Now it must be determined how much nitrogen any construction projects will release. This issue delays or postpones about a quarter of building projects.

The list of these issues goes on and on, and I got bored writing about them all. Suffice it to say: there are lots of hard-to-untangle obstacles to building new homes.

Getting creative

Since construction is a mess, de Jonge is now looking at more creative solutions to create space within the existing housing stock.

In April, the cabinet launched a 300 million euro program to stimulate the building of pre-fabricated homes, which circumvent many of the problems with construction. (But still leave municipalities with the problem of where to put them.)

Last week, de Jonge said he thinks between 80,000 and 260,000 new homes can be created in existing homes and vacant buildings, by: “topping,” building an extra floor on roofs; dividing homes; homeowners renting out vacant rooms; converting outbuildings or sheds into homes; and changing municipal regulations to allow home owners to add tiny homes for their children (for example) in their gardens.

The bottom line

The Dutch housing shortage is the result of the deliberate choices—a reliance on hands-off, free-market principles.

It was a predictable disaster that developed and will continued to happen in slow motion. Many lives, families, careers, and futures will be put on hold in this country because people don’t have homes of their own.

It’s very American of me to want to end this story on a positive note… and who knows if any de Jonge’s polices will work. Maybe “topping” is a ridiculous plan; maybe only a fraction of 900,000 homes will be built in the next seven years.

But I must say! It’s a positive sign that even within the current Rutte cabinet de Jonge is changing course, admitting to the public that something went seriously wrong in the past to get us where we are today, and taking a pro-active, hands-on leadership position.

🥳 LEUKE DINGETJES

The Versailles of the North

The Dutch royal palace of Het Loo has completed a 171 million euro renovation.

“The palace was built in 1686 as a royal hunting lodge for King William III and Queen Mary on the outskirts of the city of Apeldoorn in the heart of the Netherlands. It remained a summer retreat for the House of Orange well into the 20th century. Queen Wilhelmina stayed there after the Second World War until her death in 1962.”

So much for the Dutch royals being low-key! Via the Art Newspaper.

Putin’s Dutch former son-in-law in (even more!) trouble

“Dutch prosecutors have seized a plot of land near Amsterdam that belongs to Vladimir Putin’s former son-in-law… the plot of land in Duivendrecht is owned by Jorrit Faassen, a Dutch businessman who was married to Maria Vorontsova, the Russian president’s elder daughter.”

Faassen, who lives in Moscow, was recently questioned at Schiphol for sanctions evasion. via the Guardian.

Two new Dutch tracks on repeat this week

I couldn’t pick! First: a banger from Roos Blufpand about being too old for the club.

Second: “Queen’s Pleasure is an impertinent britrock band from Amsterdam.”

I had no idea re: dutch former son-in-law eek